Seventeen months before Jacksonville Sheriff’s Officer Tim James was charged with repeatedly punching a handcuffed teenager, he openly bragged about “ass whoopin” someone else he arrested.

“Someone just learned a hard lesson about not showing your ass in Jacksonville,” James wrote in a January 2016 Facebook post. “(Three) felonies 2 misdemeanors and an ass whoopin to boot. Lol. I love my job.”

That post and others landed James under investigation, but he received only a written reprimand and no suspension.

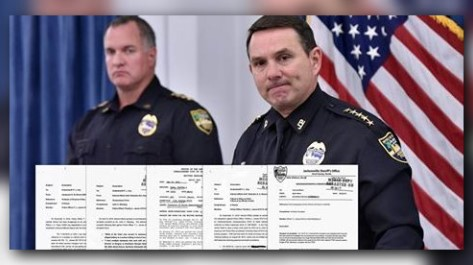

Last month, James was charged with striking 17-year-old Elias Campos in the face between four and six times as the teen sat handcuffed in the back of his patrol car. James’ sergeant, who reported the incident, said he commanded the officer multiple times to stop. James has since pleaded not guilty. He and his attorney could not be reached for comment.

James’ arrest was the violent crescendo of a troubled career. Over the course of three years, he had been investigated by the Sheriff’s Office at least 11 times. Seven of those complaints were sustained.

The history of James underscores what’s at stake as Sheriff Mike Williams promises to rein in cops who show a pattern of violence. His case also illustrates how an officer can turn increasingly violent, despite operating under numerous layers of oversight.

The consequences of the investigations into James were meted out under the sheriff’s “progressive discipline policy,” aimed at making repeat offenders subject to harsher penalties.

For James, his most severe punishment was a 10-day suspension for lying to supervisors. It came before three additional sustained complaints, including the Facebook posts.

That’s because James was getting in trouble for different categories of offenses. Under the policy, James’ punishment for lying wouldn’t influence the punishment he received for a firearms violation.

Seth Stoughton, a former Tallahassee police officer who is now a law professor at the University of South Carolina, said the problem with the way departments institute progressive discipline policies is “that’s not how misconduct works.

“Someone who is a habitual rule breaker doesn’t confine themselves to breaking one rule,” Stoughton said.

Not everything is left up to human judgment. The Sheriff’s Office also uses a data-driven early detection system to watch for officers who might need intervention based on the frequency of complaints against them, use-of-force incidents, work absences, and other metrics.

Citing state law, Williams said he couldn’t comment on James. But earlier this year, the sheriff promised to reform the “early warning system” after the city settled a civil lawsuit stemming from a controversial police shooting. Two former Jacksonville officers, including the one responsible for the shooting, spoke to the system’s ineffectiveness in depositions before the suit was settled.

Williams stressed that his sergeants, and not the warning system, are his most important defense against officer misconduct.

Sergeants check in with officers at the beginning and end of each shift. They oversee the paperwork. They know, or at least should know, what their officers are up to, and they are the people most likely to sense when something isn’t right.

“If anybody is going to see anything in terms of an issue that’s bubbling up with an employee,” Williams said, “it should be this group of people.”

A ROCKY START

Some details of James’ past remain unclear.

The Sheriff’s Office said it could not answer any questions about the officer, citing the “Law Enforcement Officer’s Bill of Rights,” a state statute that prevents the public from knowing about pending investigations into officer misconduct.

The Times-Union requested James’ use-of-force reports on June 30. The reports would indicate whether James used violence often enough to set off an early warning system alert. The Sheriff’s Office has not yet responded to the request.

James’ personnel file, however, reveals a history of questionable judgment throughout his career in Jacksonville.

He was hired in January 2014. A little more than a year later, James allowed a detainee to step out of his pants and stand naked outside the Pre-Trial Detention Center’s intake door.

James then led the man through the intake door and into the shakedown area, according to an investigator’s report.

The detainee “continues to stand there totally nude until the handcuffs are removed and he is eventually provided with inmate clothing,” the report said.

It concluded: “Officer James had an obligation to adequately control his prisoner and take positive action to prevent him from embarrassing himself and exposing other prisoners and agency personnel to [the detainee’s] undignified appearance.”

In July 2015, James had just divorced his wife when he was barred by his supervisors from visiting his girlfriend, then a recruit, at the Police Training Academy. A month later, he disobeyed that order. When questioned, he lied three times.

The recruit, Kathleen Camacho, is now his wife. In the following months, she would be at his side during at least three incidents that came under investigation. She was the only witness in a use-of-force probe that exonerated James.

In a November 2015 report about the Training Academy incident, the Sheriff’s Office hit James with “failure to obey an order” and “failure to be wholly candid.” James’ lieutenant said he was “flabbergasted” and “very disappointed.”

He received a 10-day suspension, the harshest punishment he would get, until his recent arrest.

‘I LOVE MY JOB’

About a month after the 10-day suspension, James took to Facebook.

In January 2016, he boasted of giving someone an “ass whoopin” along with three felony charges and two misdemeanors, adding: “I love my job.”

The Times-Union on June 29 requested James’ arrest reports from a two-day period around the time of the posting and has not yet received a response from the Sheriff’s Office.

A week later, James posted again: “Yep it’s that kinda night already. Someone’s getting a size 13 boot to the ass.”

The next day: “JSO. Dirty deeds done dirt cheap.”

The day after that: “How I’m spending the super bowl. Sitting in the ghetto making that off-duty dollar.”

The posting streak concluded with a threat to any who would ask him for directions while he was working security on a road blocked for construction.

“If you ask me ‘can I go this way’ I’m going to drag your ass out of your car through your window and monkey stomp you!” James said.

He added: “#realtalk.”

In May 2016, the Sheriff’s Office gave James a warning. His Facebook posts, the investigator said, were “unacceptable.”

“It is the policy of the Office of the Sheriff to ensure that discipline is positive and progressive in nature,” the investigator’s report said.

What followed was in bolded type: “Any further misconduct on your part could lead to demotion, suspension, or dismissal.”

‘FURTHER MISCONDUCT’

Just three days before issuing that warning, the Sheriff’s Office opened another James investigation.

A nurse anesthetist claimed to have lost 75 percent of the function in his arm, inhibiting his ability to work, after James took him to the ground while arresting him.

The take-down happened as James was working off-duty at a Pearl Jam concert alongside Camacho, whom he would marry in August 2016.

The nurse, John Blessing, dropped his complaint and refused to cooperate after consulting with an attorney. He declined to comment on this story after consulting the same attorney.

The Times-Union could not locate any civil complaint filed by Blessing, but a judge dismissed the charges — resisting without violence, disorderly intoxication and battery. Blessing had successfully argued that James didn’t properly investigate the alleged crimes or establish probable cause.

In July 2016, a Sheriff’s Office detective exonerated James for the Blessing complaint. Camacho was the only witness listed in the detective’s report.

In November of 2016, James reported his handgun stolen. A citizen found the firearm on a highway on-ramp the next day.

James told investigators the weapon had gone missing from his patrol vehicle, which was parked in his driveway. He said his rear windows were open, and he speculated that nearby lawn maintenance workers took the gun.

Investigators hit James with a 2-day suspension and a written reprimand for a violation of the Jacksonville Sheriff’s Office’s firearm policy, which prohibits leaving firearms inside the cabin of a police vehicle.

‘BOLEO’

In April, James made a forceful arrest that generated headlines.

James encountered 21-year-old Daniel Nyman while working off-duty at UF Health Jacksonville. Nyman was shouting loudly at his mother, who was trying to have him committed to a mental health facility.

The ensuing conflict between Nyman and James was captured on smartphone video.

When James approached Nyman, the young man shouted at James while throwing his hands in the air and backing away.

James then spat at the ground as Nyman had his back turned toward him.

Nyman waved his arms. James took him to the ground.

The officer charged Nyman with resisting with violence and battery on a law enforcement officer, or “BOLEO.”

Meanwhile, James’ wife, Camacho, tackled Nyman’s mother as she approached the confrontation.

Prosecutors reviewing the case later dropped the charges. The video footage, they concluded, didn’t support what James had told them.

James had claimed Nyman tried to take a swing at him. His wife said the same thing. Prosecutors saw no evidence of that.

What they did see was James spitting at Nyman, not Nyman spitting at James, as the officer had claimed.

Prosecutors concluded that Nyman’s arm movement was “consistent with a display of anger,” not violence.

“If Ofc. T. James was hit by spittle, it likely happened when Ofc. T. James got right in [Nyman’s] face, which fails to establish an intentional act by [Nyman],” the State Attorney’s Office said.

They also cited the June arrest of James, saying it would make the officer “subject to heightened impeachment at trial.” James’ wife, too, would have her credibility questioned at trial, the prosecutors determined.

HUSBAND AND WIFE

In both the Blessing incident after the Pearl Jam concert and the confrontation with Nyman in April, James was working off-duty security details alongside Camacho, who now goes by Kathleen James.

The practice of spouses doing police work together is unusual. It’s frowned upon in part because of what ended up happening with James — his girlfriend, and later his wife, became a key witness in at least three investigations.

“I think that may be a little too much to expect from a spouse,” Stoughton, the law professor, said. “You avoid putting officers in that situation by saying, ‘Look, you’re not working the street together.’”

Lt. Chris Brown, of the Sheriff’s Office Professional Oversight Unit, said the agency doesn’t have a policy explicitly prohibiting couples and spouses from working together.

In reviewing all the investigations into James’ conduct, Stoughton said his first major red flag would have been the Training Academy incident. He described it as “telling a material lie in the context of a disciplinary investigation,” which should have called the officer’s honesty into question for future probes into alleged misconduct.

“In my view, you shouldn’t be allowed to be a cop after that,” Stoughton said.

Relatively few officers are responsible for the vast majority of misconduct, Stoughton said, which makes it even more necessary for police departments to catch repeat offenders and get them off the street.

“The problem is, it’s very difficult to do that,” Stoughton said.

The Law Enforcement Officer Bill of Right’s is one hurdle, Stoughton said. Departmental policies such as progressive discipline are another. Police union contracts, he added, have grown increasingly focused on safeguarding against investigations, adding to the difficulty of firing officers who might run afoul of the rules.

“That means that police chiefs don’t always have the ability to discipline and terminate officers they’ve identified as problem officers,” he said.

BEHIND THE WHEEL

By the time James struck and killed a pedestrian on University Boulevard in May, he already had a history of incidents behind the wheel.

They included two chargeable traffic crashes and twice running red lights since he started with the Sheriff’s Office in 2014, and eight total traffic tickets since 2002.

James struck the pedestrian, Blane Land, in the course of responding to a robbery call. Land, who would have been 63 last Wednesday, died.

The Sheriff’s Office said James did not have his emergency lights on because he was not the primary officer responding. After the crash, Assistant Chief Chris Butler said that Land ran in front of the cruiser.

“It might be something where he’s just running out in front of the cars, maybe got confused or something like that,” Butler said.

Butler added that investigators also were not ruling out a suicide attempt.

Two months later, the cause of the accident hasn’t been made public. The Times-Union requested the traffic homicide report Thursday but hasn’t received it.

Stacy Land, Blane’s youngest sister, said her family would have been understanding if Blane’s death was explained as a tragic accident. But the suggestion he might have committed suicide, she said, shocked and saddened her family.

“It’s like they killed him twice,” she said. “Why leave the family with that image?”

Land said her brother was not in any way suicidal. He lived in Pensacola taking care of their elderly parents, she said, and was in Jacksonville on IT-related business. The Land family has since learned about James’ history from media accounts.

Stacy Land pointed to the incident at the hospital, calling James a “victim blamer.”

“If somebody would have paid attention, would he have had the chance to hit Blane?” she said. “The best we can do is hope that they tighten up their controls. He shouldn’t have been on the street.”

TIGHTENING CONTROLS

It was just months ago that Sheriff Williams highlighted the importance of catching problem officers before people get hurt.

He recently said his reforms to the early warning system, which include increased oversight and new emphasis on yearly reviews of officers, should happen in the next 60 days.

The annual reviews will help the Sheriff’s Office look at an officer’s use-of-force incidents or complaints in aggregate rather than on a case-by-case basis. They are part of a greater effort to look at the “big picture,” the sheriff said.

In April, the early warning system was at the center of a $1.9 million settlement by the city of Jacksonville for the 2012 police shooting of Davinian Williams, an unarmed black man who was shot and killed by a former Jacksonville patrolman during a traffic stop. The lawyer representing Williams’ family argued that the system should have flagged the officer for his frequent Taser usage.

After the settlement, Sheriff Williams wrote a personal apology to the family, promising to reform the warning system. He told the Times-Union that his efforts are focusing on the chain of command overseeing the system and the way supervisors respond to early warning alerts.

Rufus Pennington, the attorney who represented the Davinian Williams family, said the idea behind the early warning system is to watch for the frequency of the investigations, both founded and unfounded. That way, supervisors are alerted even if investigators are getting it wrong.

But the system, Pennington said, is “only as good as the effort the department puts into it.”

Andrew Ferguson, a law professor at the University of the District of Columbia who studies how data impacts policing, pointed out that federal investigations of early warning systems in Chicago and Baltimore concluded that those, too, had fallen short.

“They generally have been put in place for good reasons, with good intentions,” Ferguson said. “But the follow-through in many cities has not been compliant with the expectations. In many ways, they have failed.”

Sheriff Williams stressed that the warning system is only a tool. Sergeants need to be unafraid, he said, in asking officers prying questions.

“Don’t wait for an early warning system message to come out that you need to talk to Officer Jones,” Williams said. “If you see something in his behavior, you have every right to step to this guy and say, ‘Hey, what’s going on?’”

It’s unclear if James ever received that type of intervention from his sergeant, but at least one person close to him noticed a change in his behavior.

In the days after his arrest in June, his ex-wife filed for an emergency custody hearing.

She expressed concern about the safety of their children and asked that James be prevented from seeing them until he submitted to a mental health evaluation and a drug test for anabolic steroids.

James’ ex-wife pointed to the incident at UF Health and the most recent arrest. She said she believed James “has had some manner of break in his mental health.”

They had conversations, she said in court filings, where James “expressed no remorse concerning these recent work-related incidents.”

You can read the original Florida Times-Union article here.

Ben Conarck: (904) 359-4103; Andrew Pantazi: (904) 359-4310