The Vietnam War was a long, costly armed conflict that pitted the communist regime of North Vietnam and its southern allies, known as the Viet Kong, against South Vietnam and its principal ally, the United States.

This extremely diverse war, increasingly unpopular at home, ended with the withdrawal of U.S. forces in 1973 and the unification of Vietnam under communist control two years later.

More than 3 million people, including 58,000 Americans, were killed in the conflict.

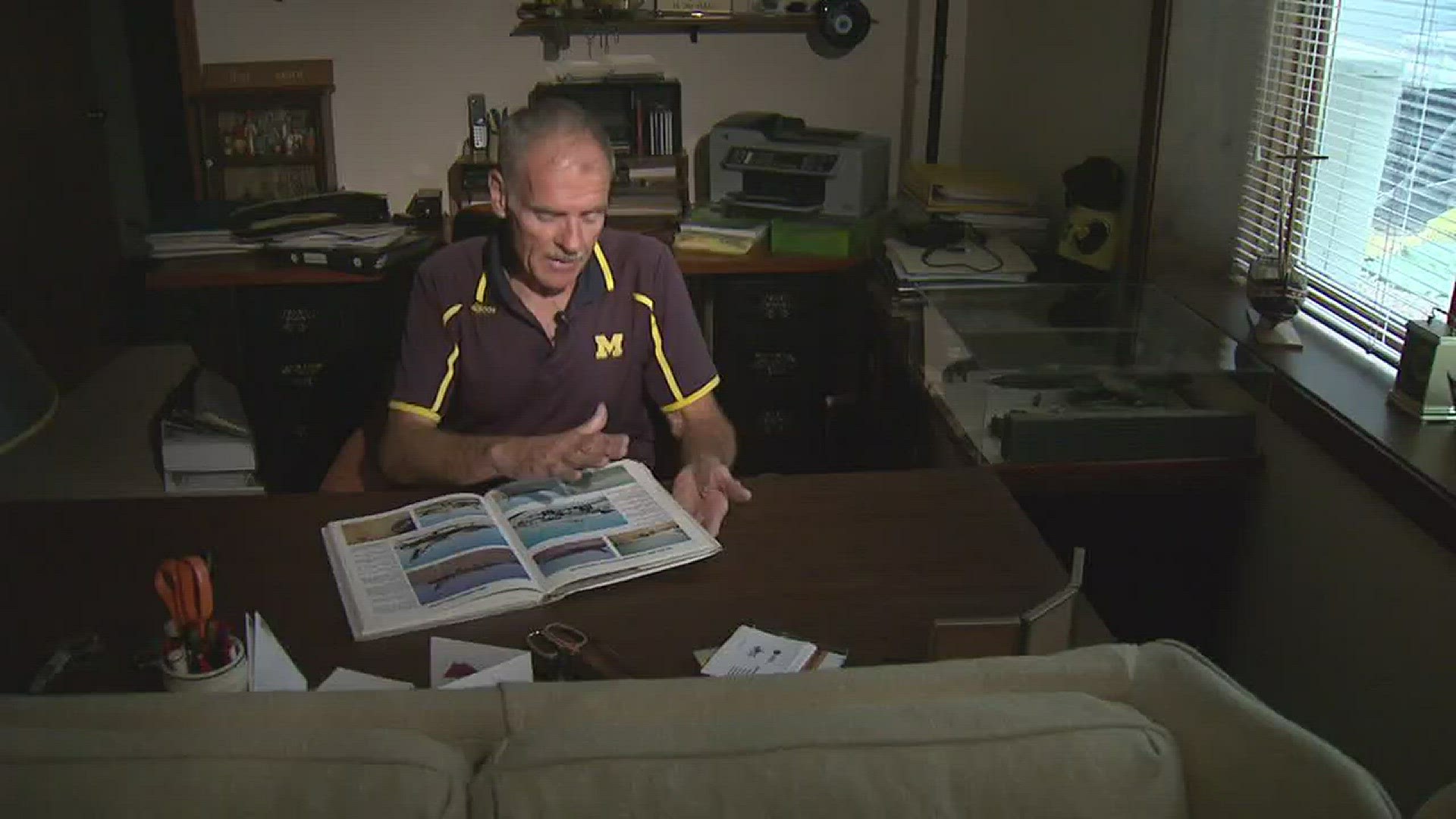

“We knew how we could have ended that war in Vietnam, and won it, but we weren’t quite allowed to do that,” said retired United States Air Force Lt. James DeVoss from his Grand Rapids home. “We gave it our best shot, the only bad part is too many died trying.”

DeVoss, a Grand Rapids native, piloted an F-105 Thunderchief (Thud) during his time in Vietnam. He was considered one of the best fighter pilots in the United States’ fleet.

His F-105 was shot down during a bombing-run over northern Laos in 1969. Thanks to an amazing and skilled group of para-rescue jumpers, he survived and because of it, to this day, continues to share his story.

“A lot of ‘bad’ happened over in Vietnam; there’s no doubt about that,” DeVoss said. “But plenty of ‘good’ happened over there, too, and that’s why I like to share my story so much, so people can learn of the ‘good.’”

DeVoss says his love for the aircraft, and flying, developed at an early age.

“The first time I heard an airplane, I was captivated by them,” DeVoss said. “If I heard one, I had to search the skies until I could see it, and I had to watch it until it went out of sight.”

DeVoss would join the Air Force, go through pilot and ejection training, and when the Vietnam War started, he was sent to Southeast Asia to follow orders and fight for his country.

This is a copy of the official United States Air Force report on the on Jim DeVoss’ mission from June 16, 1969. It details everything that happened, as well as lists all the names of the para-rescue jumpers who saved DeVoss’ life in the jungle that day.

Little did DeVoss know, what he learned during ejection training would be a life-saving education.

“We always flew with a checklist,” DeVoss said. “And in that checklist was what you were supposed to do whenever anything went wrong with the airplane.

“You have to do all the things on the checklist in the exact order they’re listed, or you die.”

DeVoss had flown 70 successful missions, during his career in the cockpit, but his 71st mission – on June 16, 1969 – didn’t go like the rest.

“It was an early morning go,” said DeVoss, as he began to detail his last mission. “I got up at 3:30 in the morning, had breakfast, then I went over for about an hour of pre-flight (discussion about what the mission would be).

“My flight commander said, ‘Jim, it’s about 15 missions early, but you’re ready for flight-lead checkout; you’ll lead the mission; start briefing.’”

DeVoss says the mission was to fly over northern Laos, and blow holes in the roads along the Ho Chi Minh Trail, hoping to prevent the enemy of driving trucks full of supplies from North Vietnam, through Laos, down to South Vietnam.

“When we got airborne and started the mission,” DeVoss says, “everything was going as planned, and I ordered us to do one more pass.

“All of the sudden, my fighter became wobblier and wobblier; I checked around the cockpit, and saw nothing wrong, so I wasn’t sure what was going on.”

DeVoss then said, “The nose of the plane started to do funny things, and the lights on the control panel started coming on.

“I remember seeing enemy fire coming up at us from the ground,” DeVoss said. “Once I saw the hydraulics light come on, and then knew that my primary first and second backups were gone, I knew I had been hit.

“I had no more PSI (Pounds of air per Square Inch) to move any of my flight controls, and I was seeing indications that I was starting to lose power, because I was getting really close to stall-speed.

“There’s a big button on the left side of the cockpit, and when you push that button, the wing tanks blow off as well as the racks that hold the bombs,” DeVoss adds. “Everything pretty much gets blown off the plane to lighten it, allowing for as much airspeed as possible.

“After that happened, the airplane went from 15 degrees nose-high to 45 degrees nose-low. All of the sudden, I was plastered up against the cockpit, undergoing about two negative G’s (G-Force/weightlessness).

“I immediately knew the airplane wasn’t coming out of this, and if I’m going to have any chance at getting out of it, I needed to somehow fight the G-Force and get my butt back in that seat, despite the fact that the plane is literally falling out from under me.

DeVoss says pieces of the plane began tearing off as it continued to tumble rapidly toward the ground.

“It got wobblier and wobblier,” DeVoss said, describing the plane while it was diving. “Two-hundred and fifty knots or lower, there won’t be a problem with ejection; 250 to 500 knots, there’s sufficient wind hitting your body that it will cause it to start twisting and turning, bending and breaking.

“Over 500 knots, the textbook says its lethal, and you’re going to die, because the wind hits your oxygen mask which covers your nose and rips it off; the wind goes into your nose, which you can’t close, it over-expands your lungs, they rupture, and you bleed to death instantly.”

DeVoss says he remembers traveling toward Earth, through 1,500 feet, at 700 knots.

He had no choice but to eject, and either die trying, or somehow miraculously survive.

“The ejection is like five pounds of TNT (dynamite) going off under your seat,” DeVoss said. “If you don’t have your butt firmly strapped into the seat, it will compress your spine.

“I reached down, hit the handle, squeezed the trigger, and boom – up I went. I was immediately pushed 250 feet into the air, while traveling at 700 knots.

“One second after the explosion occurs, three things happen simultaneously,” DeVoss said. “You’ve got a lap belt, shoulder harness apparatus that’s holding you into the seat; it blows apart.

“Simultaneously with that, on the front of the seat and the back of the seat are two take-up reels with a strap in between; they spin in opposite directions and that strap straightens out and it pitches the pilot forward out of the seat.

“The third thing, a little piece of lead is fired out the back of the seat, which pulls out a drogue-shoot. What it gets is man-seat separation so that your canopy opens and your seat doesn’t tumble into it, and you.

“My challenge was airspeed; as I separated from the confines of the cockpit, all of the sudden, I had 700 miles an hour of wind hitting me.

“My visor wasn’t strong enough to withstand the wind blast; it shattered and blew back into my face.

“The next thing that happened is the wind hit my oxygen mask; it pushed it back and the soft, rubber blackened both of my eyes, and cut me under the neck.

“As the wind hit my shoulders, they were both slammed back, and both were immediately separated.

“There’s a device that was designed, as your arms were pushed back by the wind during ejection, to catch your elbows and cause your arms to tuck in. My right arm tucked in, but the left one did not. It slipped out, and went around behind, shattered, and beat against the back of the seat.

“As I continued up, the wind hit my torso, with my feet still in the chair. Both hips were immediately dislocated, because 14 positive Gs (G-Force) is what you get in an ejection.

“The wind hit the tops of my boots and tucked my feet under the seat, and that separated both my knees. In the right knee, every tendon, every piece of cartilage, every ligament was completely torn apart.

“One nerve; one blood vessel with some skin around it, was all that remained to keep my lower leg alive. Another 8th of an inch, it would have ripped apart, and I would have bled to death.

“The left leg suffered a similar fate, except the Patellar Tendon, the major one, was only three-quarters of the way torn through. Everything else was torn apart.

“I landed in a bamboo patch, catching the top of the bamboo. The parachute must have slowed me down a little more before I thumped on the ground. The bamboo shoots impaled me, so I had that injury to deal with, too.

DeVoss landed 130 miles behind enemy lines. He was unconscious.

“After I landed and regained consciousness, I really thought my arm was still in the cockpit,” DeVoss said. “I immediately heard my wingmen above me; they made the radio call for help.”

DeVoss said a search and rescue effort was immediately launched from a nearby command post.

“I laid there in the bamboo for about 90 minutes,” DeVoss said. “Helicopters were scrambled and flew immediately to the location where I was down.

“During my rescue, the choppers took enemy fire 13 separate times,” DeVoss said

DeVoss said he kept drifting in and out of consciousness for the hour-and-a-half he was on the ground.

“The Jollys (Helicopters) arrived at my location, and para-rescue jumpers began coming down to get me,” DeVoss said. “Those guys had an intensity about them, and they’re always determined to get you out.

“Once I was lifted safely into the Jolly (helicopter), we immediately raced out of the area. I was told later that the whole rescue operation only lasted 10-15 minutes.”

DeVoss says he was immediately flown to an Air Force base in Thailand.

“I was in surgery almost immediately,” DeVoss said. “I was told I quit on them twice, but they managed to bring me back both times.

DeVoss says he endured several surgeries, repairing everything that was broken on him during the ejection. He says he was told initially he wasn’t going to make it, but he found a way to defy those odds.

“I think about it every day, and it really gets me,” said DeVoss, with tears welling-up in his eyes. “They were my heroes – the PJs (Para-Rescue-Jumpers) who came out there to get me, at full risk of their life.

“My healers were the doctors and nurses, and everybody in Thailand, who helped me get through six months of physical therapy, and for a few additional years after that.

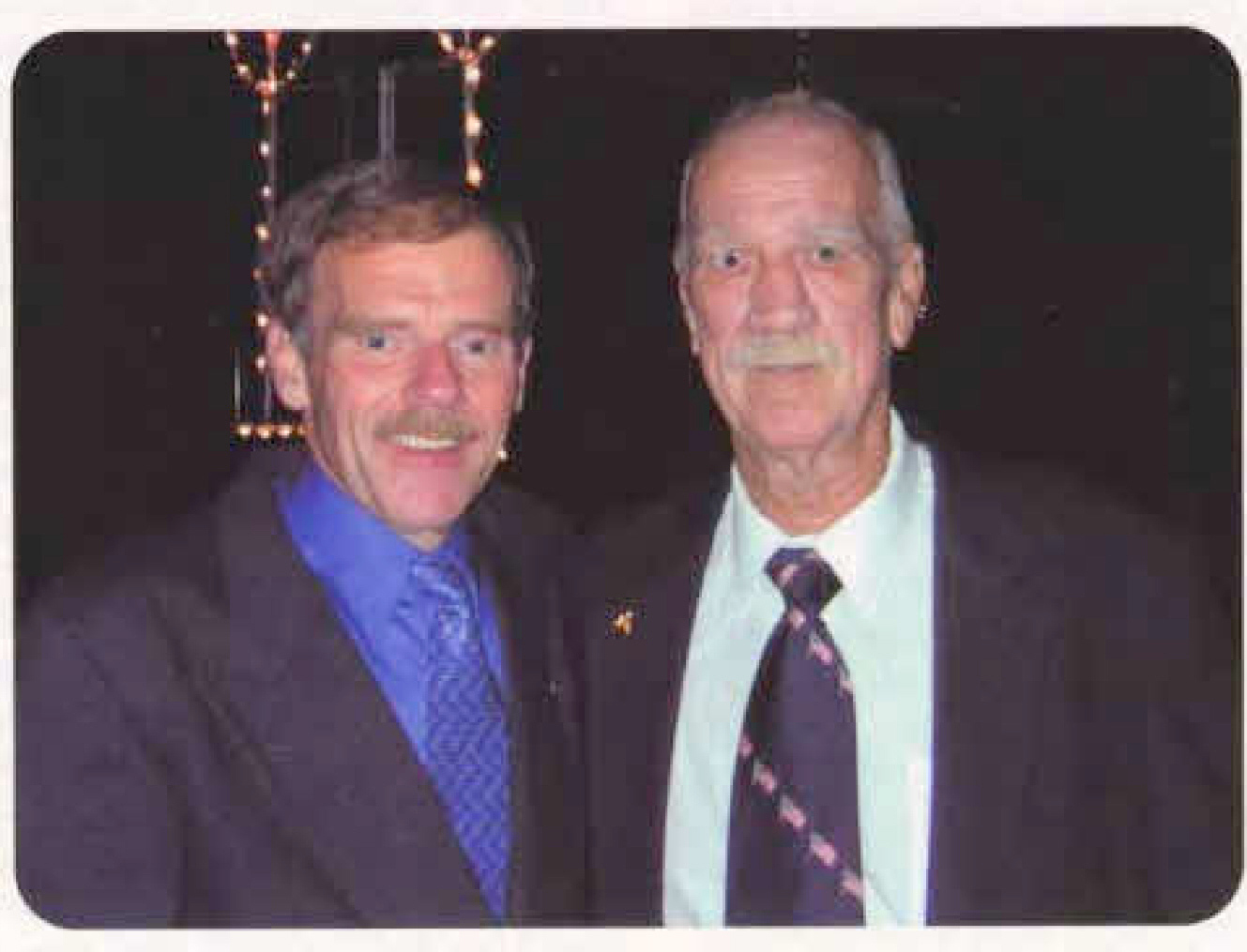

For several decades after his rescue, DeVoss said he was forbidden to meet any of the para-rescue jumpers who pulled him out of that bamboo patch in Vietnam. DeVoss says he was doing a speaking engagement in Tampa, Fla., on Dec. 10, 2001, when all of the sudden a man started walking down the aisle toward DeVoss, who was on stage.

The man’s name was Lorenzo Willis, and he happened to be the PJ (Para Jumper) who initially dropped from the helicopter into the jungle to assess DeVoss’ condition.

The two hadn’t seen each other, until that day – 32 years later.

DeVoss said once Willis revealed his identity, he came off the stage and ran into the arms of Willis. The two embraced for quite a while.

“As much distaste and animosity and hatred there was for the Vietnam conflict, still, if there was an American who needed help, there were others that were ready, willing and able to provide that help,” DeVoss said. “Nearly 47 years later, every day, I thank my heroes (Para-Jumpers), my healers (nurses and doctors) and my enablers – the American people.”

If you know of a story that would make for a good “Our Michigan Life”, send an email to: life@wzzm13.com

“Our Michigan Life” airs weeknights on WZZM 13 News at 6.