JACKSONVILLE, Fla. — The year 2020 has brought the challenges of a pandemic and a cry for social and racial justice.

In Jacksonville, an interracial couple was surprised when the appraised value of their home shot up after making a simple change that pointed to racism.

After a disappointing appraisal, the couple changed their interior decorations, which reflected an Afro-centric culture, to reflect a European culture. The couple then had the same property appraised again, and to their surprise, the value went up by thousands of dollars.

Is racial segregation of the past a part of our present?

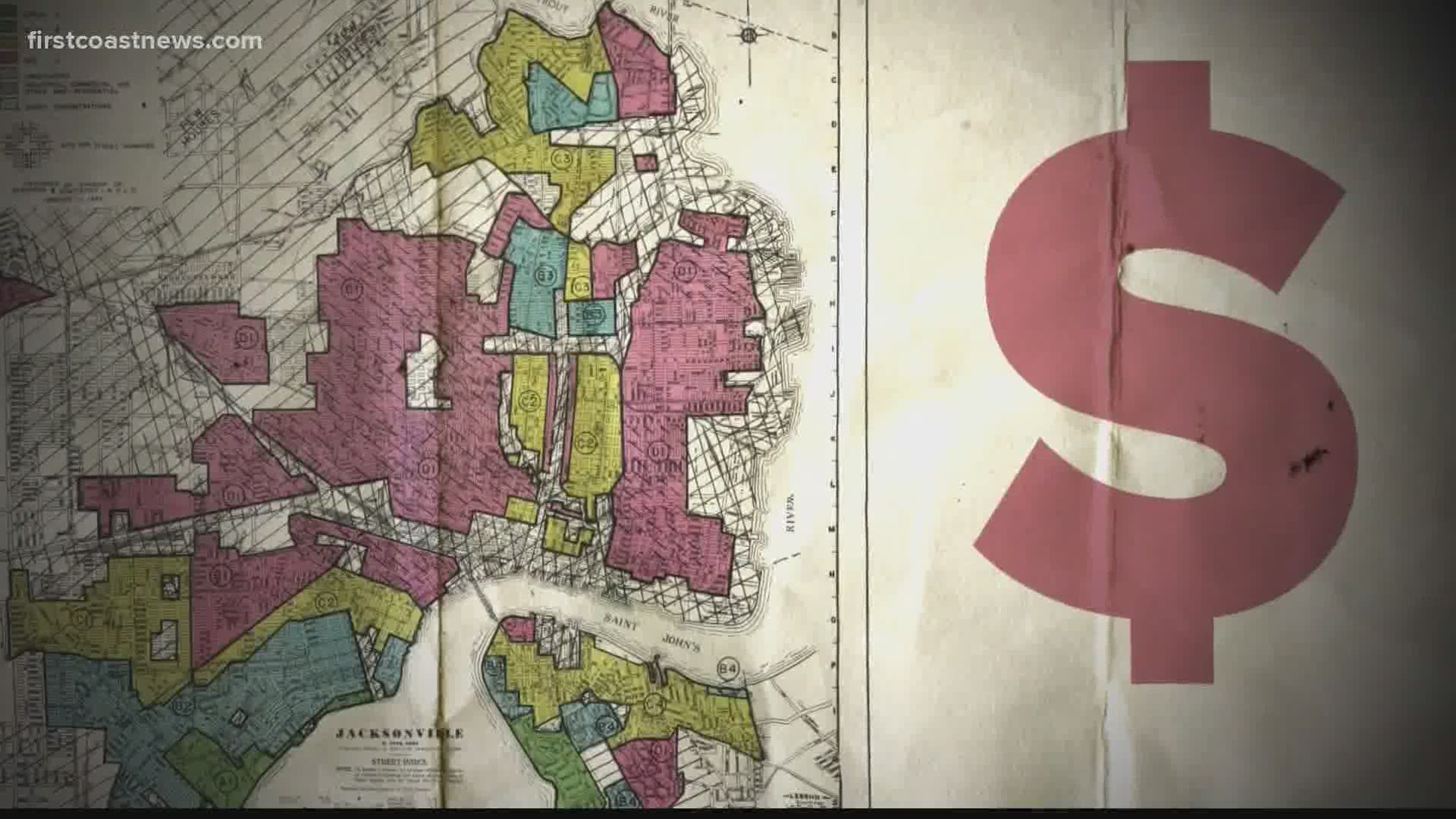

For decades, Black homeownership was made difficult through redlining practices; neighborhoods identified on real estate maps as too risky to invest, neighborhoods that were predominately Black.

The practice was created by the Home Owners Loan Corporation. It is now illegal but still has an impact today.

Where you live impacts the quality of your schools, it impacts your relationship with police and it impacts the ability to create generational wealth.

RELATED: Jacksonville couple says they faced discrimination in home appraisal because of wife's race

To understand the legacy of redlining, you have to see it from the level of a drone, at street level and through the eyes of those who have experienced it.

"We moved in October 1959," said Warren Jones. "We were the first Black family on Stockton street."

Warren Jones, former city council member and chair of the Duval County School board, grew up in a neighborhood two blocks from Mixon Town.

"We were considered living on the other side of the tracks," he said.

Jones said redlining has plagued communities with poverty, crime and health-related problems.

"There is a tale of two cities in Jacksonville," Jones said.

Jones a husband, father, grandfather and an inactive realtor has seen it from every angle.

"We now know why we were limited to where we could live," he said.

The redlining maps were created in 1933 by a federal home loan agency, marking in red-ink areas where the government would not lend money.

Those maps labeled or identified Black neighborhoods as "hazardous."

The maps created zones where homeownership, and the generational wealth created by owning property, was all but impossible.

"A lot of people recognized they could not get loans but did not know what was causing it," he said.

Redlining was banned with the passing of the 1968 Fair Housing Act, however, its legacy or consequences were left behind.

"You have neighborhoods that are still struggling," he said.

Jones remembers living in a community restricted by the invisible fence of racial segregation.

"I had to go to Forest Park because the school system was segregated," he said.

And his neighborhood school in his redlined community was built near a number of environmental hazards.

"Forest Park was built in the same block with the incinerator that burned all of the garbage in Jacksonville," Jones said. "In the same block where they had the dog pound that killed dogs, and a slaughterhouse, and a poultry house where chickens were slaughtered."

Jones says the children played in two open areas near McCoy's Creek, which at the time was a cesspool of human and animal waste.

"That creek at the time was the sewer line for the Westside of town," Jones said. "Everything ran into it, from raw sewer to the waste from the slaughterhouses."

We went back 60 years to the neighborhood where Jones grew up to see the legacy of redlining and how the communities are lacking.

"If you walk down this street, there is no infrastructure, no curb and gutters, very few sidewalks," he said.

Today, a number of homes have been demolished.

Many of the environmental hazards are gone, and while those who were able to move have moved, Jones said the community is now plagued by poverty, crime and illness.

There are no grocery stores, very little access to health care and property values are low.

"Homeownership is the key to growing wealth, unfortunately, many people do not have that advantage," Jones said.

Studies have shown that almost all redlined neighborhoods are worse off today.

In some, life expectancy is nearly 20 years less than residents of affluent neighborhoods.

"There are many neighborhoods that have been left behind," he said.

What will it take to erase the vestiges of redlining in predominately Black neighborhoods?

Jones said first there has to be a commitment along with an investment.

"We need to redouble our efforts to make sure we invest in those neighborhoods to make sure people can be lifted up and feel proud and be willing to invest in those neighborhoods going forward," he said.

DIGGING DEEPER

- The roots of structural racism: On Your Side's David Jones looks at how Redline maps reinforced the city’s original 1930 zoning map – a document that designated where dumps, slaughterhouses and polluting industries would go. WATCH First Coast at 11 p.m. Thursday

- Racism in real estate: Investigative Producer Anne Schindler explores how racial bias impacts Black Realtors and homeowners alike – taking both a financial and a psychological toll. WATCH First Coast News at 6 p.m. Friday